ARRIVAL IN AUSTRALIA – THE WHITE AUSTRALIA POLICY

In the immediate post-war years Australia launched a bold immigration program to increase the size of its population: a large workforce would boost economic development; more people could better defend the country.

Initially Australia encouraged people from the United Kingdom and Displaced Persons from war-torn Europe to come. Through the 1950s Australia negotiated migration agreements with several European nations such as the Netherlands, Italy, Germany, Greece, Malta, Austria, Spain, Belgium, Finland and the Scandinavian countries. Other countries were to follow.

Mass migration from what were termed ‘non-British’ sources helped transform the size and make-up of the Australian population.

The Australian Government established temporary accommodation centres for the newcomers, usually in former defence establishments. Reception Centres were to provide for ‘the general medical examination and x-ray of migrants, issue of necessary clothing, payment of social service benefits, interviews to determine employment potential, instruction in English and the Australian way of life generally’. Holding Centres were needed to house non-working dependants when Reception Centres could not cope with the large numbers arriving between 1948 and 1951. Specially built hostels housed workers close to their places of employment in places like Wollongong and Newcastle.

The largest and longest-lasting Reception Centre was at the former Bonegilla Army Camp on the border between New South Wales and Victoria. When the Displaced Persons scheme began to fall away, Bonegilla received and processed assisted migrants and refugees – almost all from non-English speaking countries. Altogether over 300,000 people entered Australia via Bonegilla between 1947 and 1971.

At the end of December 1947, 839 young men and women from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania arrived at Bonegilla as the first contingent under the International Refugee Organisation’s Displaced Persons program. They had been carefully selected to make a good impression for the Minister for Immigration, Arthur Calwell, who wanted to ensure that the Australian public would support his mass migration program. The press described them as attractive, cheery, eager to work, adaptable and neatly clad. They were ‘particularly good types’. For a number of years thereafter all non-British arrivals were commonly known as ‘Balts’ irrespective of their nationality. They were also referred to as ‘DPs’, ‘reffos’ or ‘Eastern Europeans’.

One young teacher of English, Alan Hodge, remembers later contingents of Displaced Persons as different from the first 839 ‘Beautiful Balts’. They were often dispirited, having lost all they had ever owned and sometimes their family as well. Groups arrived fitted out in similar clothes, carrying cheap cardboard suitcases and a bag of toilet articles supplied by the Red Cross.

Bonegilla was big. At one time it could accommodate 7,700 people, with an additional 1,000 in tents, if need be. Through 1950 about 1,000 migrants arrived each week. The Reception Centre became intent on processing large numbers rather than trying to meet individual or family needs. It was not possible to accommodate family units together, and women and children were sent to Holding Centres in places like Uranquinty, Cowra and Benalla. Family separation was very unpopular.

The immediate challenges for newcomers on arrival were to gather luggage and to come to terms with the kind of accommodation that the Centre provided.

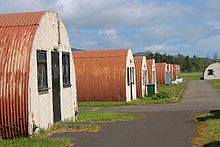

The temporary accommodation provided at Bonegilla was rudimentary. The buildings were mostly standard Army type huts which were usually unlined timber-framed huts with corrugated wall cladding and low pitched gabled roofs of corrugated iron or asbestos cement. They had been built to accommodate twenty people and had no internal partitions. They were arranged in 24 blocks, each with its own kitchen, mess huts and ablutions. Little was done to prepare the facilities for accommodating migrants in 1947.

Initially the Army provided transport, security and catering services. Army-like routines were adopted with the issue of stores such as eating utensils, linen and blankets. Army clothing was supplied when needed. The canteen and meals were arranged along military lines. The Army left Bonegilla in 1949, but in 1965 returned to occupy some blocks for training purposes.

In the midst of the huge post-war housing shortage, publicists reassured the Australian public about what was offered newcomers: the accommodation was ‘only reasonably comfortable’; the food plain, though nutritious and plentiful; there was neither luxury nor squalor. The immigration reception and settlement processes were supposed to be efficient and effective; all expenditure was carefully monitored. Australia, they declared, could feel comfortable about large-scale non-British immigration.